Frank Edward Bourne was perhaps an unlikely man to become a national hero, and to star, albeit posthumously in a blockbuster film. Born on 24 April 1853 to James, a labourer who took work wherever he could find it, and his wife Harriet, he was their eighth child and grew up in Balcombe, in Sussex (population in 1872, 880). Somehow, his mother managed to find space in their cottage to take in foster children. Frank must have gone to school, because as an adult he could read and write and helped his illiterate colleagues with their correspondence.

Life in Balcombe would not have offered anything other than a labourer’s life, and when he was eighteen, Frank joined the 24th Regiment of Foot at Reigate. He was paid six shillings a day, most of which was withheld for messing and washing. He was very quickly promoted corporal and then sergeant and just after he was sent to South Africa in February 1878, he was promoted Colour Sergeant. He was still only twenty-four: privately, his men called him ’The Kid’ or sometimes ‘Boy Bourne’.

Frank Bourne as a young man

In January 1879 the regiment, now the South Wales Borderers, was sent to Pietermaritzburg under the command of Lord Chelmsford. Thirteen companies, including Frank’s own ‘B’ company crossed the Buffalo River into Zulu country on 11 January. While the rest of the men carried on to engage the enemy, ‘B’ company was left behind at a mission post to guard the hospital stores. The mission was called Rorke’s Drift.

Frank’s ‘B’ Company

Chelmsford’s five-thousand-strong force was humiliatingly defeated by the Zulus at Isandlwana. The enemy then turned their attention to the mission. ‘B’ company, believing themselves to be safe, had done nothing to fortify the place. They made do with what they had – sacks of mealie ( Indian corn) and biscuit tins. They had about 150 fighting men plus some hospital patients.

One depiction of the Battle of Rourke’s Drift

The battle started at 4.30pm when the mission was attacked by between three and four thousand Zulu warriors. The attack continued all night. The Zulus departed the next morning shortly before the arrival of Lord Chelmsford’s relief column. Remarkably, only seventeen men of ‘B’ company had been lost. Of the survivors, eleven were awarded the Victoria Cross and four, of whom Frank was one, the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

The battle was headline news for months, every snippet of information being fed by the press to a public greedy for detail (and it has been suggested that the government encouraged this appetite, to gloss over the disastrous events at Isandlwana). The number of Zulus in the attack crept up to six thousand. One woman, an artist, wanted to paint the scene for the Royal Academy’s summer exhibition and had a miniature Rorke’s Drift built in her garden. Dozens of pictures have since been painted, the battle was even turned into a war game and Rorke’s Drift into a tourist attraction.

A Rorke’s Drift war game set-up

That the battle is well-known to so many today is in part due to the 1964 film Zulu. Frank was played by Nigel Green, incongruously nearly a foot taller than the historical figure (Frank was only 5 feet 6 inches tall; Green was 6 feet 5 inches) and much older (Green was forty at the time compared to Frank’s twenty-four).

Nigel Green as Frank in ‘Zulu’. He is wearing an Indian Mutiny medal, from 1857, when Frank was four years old.

For Frank, though, the aftermath was business as usual. As well as his DCM, which came with an annuity of £10, he was offered a commission, but turned it down as he could not afford the expense involved. He was sent to India and served in that country and Burma for the next fifteen years. On 27 September 1882, he married, in St Thomas’s Cathedral, Bombay (Mumbai), Eliza Mary Fincham. She had been born in Harwich, the daughter of a mariner.

St Thomas’s Cathedral, Mumbai – a splendid setting for a wedding

Their first son, Percy, was born hundreds of miles from Bombay, in Secunderabad, in 1883. The next son, Sydney, came into the world in Burma. At daughter, Beatrice was born on Boxing Day 1889 at Ranikhet, a hill station in Northern India.

The next year, Frank decided to take his commission, twelve years after it was offered. He was sent home, and his next child, another daughter, was born in Berkshire. Then, in May 1893, he was made adjutant of the School of Musketry in Hythe. It must have been a relief, to his wife at least, to have somewhere to call home.

The School of Musketry, Hythe, now demolished

The fourteen years in Hythe passed peacefully. Another daughter was born; Frank was promoted captain; his son Percy joined the Royal Navy Pay Office; Frank was promoted major and his son Sydney got a place at Christ’s Hospital School in London.

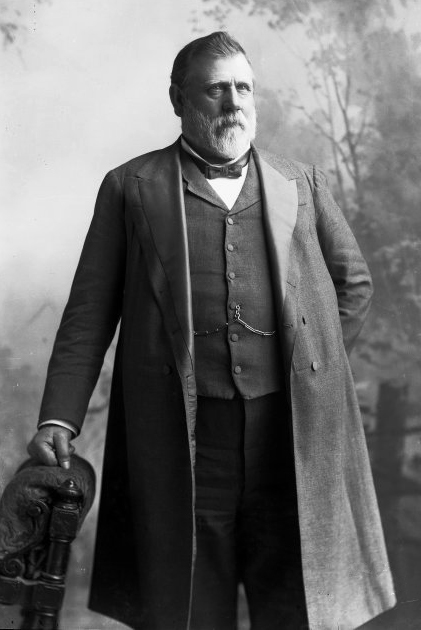

Frank in later life in a captain’s uniform

In 1907 Frank retired from the army. He seems, during his stay in Hythe, to have been modest about his South African adventure: the local press reported his role at Rorke’s Drift as part of a tribute when he left. He was also presented with a large oil painting of the battle, which he kept afterwards in his study.

He and Eliza retired to Beckenham, where he became assistant secretary of the National Miniature Rifle Club. ‘Miniature rifles’ were what is now called small bore rifles and their recreational use at small ranges had been encouraged after the Boer War in order, it was hoped, to produce a body of men who in the event of war would already be skilled marksmen.

Frank’s retirement did not last long. When war broke out in 1914, he went to the War Office and offered himself for active service but was told he was too old. Instead, he was sent to Dublin to run the new School of Musketry there. During this time he was responsible for training over 10,000 British and Irish marksmen and was rewarded at the end of hostilities with the honorary rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and an OBE.

He went back to Beckenham and miniature rifles. Both his sons had served in, and survived, the war. Percy became a Commander in the Pay Service and Sydney a stockbroker in Newcastle. There was sadness when his second daughter, Constance, died in Beckenham in 1922 and his wife Eliza in 1931.

Frank moved in with his eldest daughter. Beatrice, who was married to an architect and ran a tea room in Dorking. He died on VE Day, 8 May 1945, the last survivor of the action at Rorke’s Drift.

Frank’s grave in Beckenham cemetery. He is buried with Eliza and Constance

After his death, a blue plaque was put on Frank’s house in Beckenham

In 1936, Frank had given an interview to the BBC about his experiences at Rorke’s Drift. The original recording is not extant, but it was transcribed and can be read here:

http://www.rorkesdriftvc.com/defenders/tran.htm