In loving memory/of/ Thomas Guppy Sarsfield Hall/ born September 2nd 1844/died Janry 11th 1922

“Safe home at last”

Also of Charlotte Sophia/his wife/born April 2nd 1855/passed on Feb 26th 1933

Also of their son, Robert/Sep 15.1876 – May 1939

Also in loving memory of/their grandson/Captain Peter F.S.Dobson/4.April 1918-23 Feb. 1966.

Also of their daughter Deborah Clare Dobson/mother of the above/ 26.Jan.1883 – 7. May 1971

In loving memory of/ T E F Sangar/ the only and dearly loved son of/ the late Reverend Sangar and Charlotte his wife/ who fell asleep 15th Dec 1892

Thomas Guppy Sarsfield Hall was born at Blackrock, County Cork, the second son of Robert Hall by his second wife Sarah nee Sarsfield Head. The family were well off but as the second son of a second wife, Thomas needed to take up a profession, so when he graduated from Peterhouse, Cambridge, he took holy orders and was sent as a curate to All Saints, the parish church of Bakewell in Derbyshire. He was then sent to a country parish near Maidstone. This was apparently very damp, and his already weak chest was affected – he had suffered as a young man from rheumatic fever – so the Archbishop sent him to Hythe as curate to recover. Here he fell in love with the boss’s daughter, Charlotte Sophia Sangar, daughter of the vicar of Hythe.

During their courtship, Thomas became vicar of St Faith’s church in Maidstone town centre, but Charlotte’s father decided that the time had come for him to retire, leaving the benefice of Hythe conveniently vacant. In 1873, Thomas and Charlotte were married and he became vicar of Hythe, a post he held for the next twenty-six years.

The church he inherited was apparently very dilapidated by this time, and the low, plaster ceilings created a dark and dismal interior. Thomas studied the history of the church assiduously, and became convinced that the architects and craftsmen who had worked on the enlargement of the church in the thirteenth century had left their work unfinished, probably interrupted by the carnage of the Black Death. He decided to put matters right.

Despite general apathy, and a ‘if it’s not broke, don’t fix it’ attitude on the part of most of his parishioners, Thomas managed to enlist the interest and support of the influential – and rich – Mackeson family who lived in the town and still manged their brewery there. He raised the sum of £10,000 – perhaps half a million pounds in 2017 – and employed a top architect to remove the plaster ceilings over the nave and chancel, and in the chancel he put a great vaulted roof. It has been compared to the architecture of Canterbury Cathedral.

The remodelled chancel of St Leonard’s church

The modest plaque commemorating the work of Thomas Hall

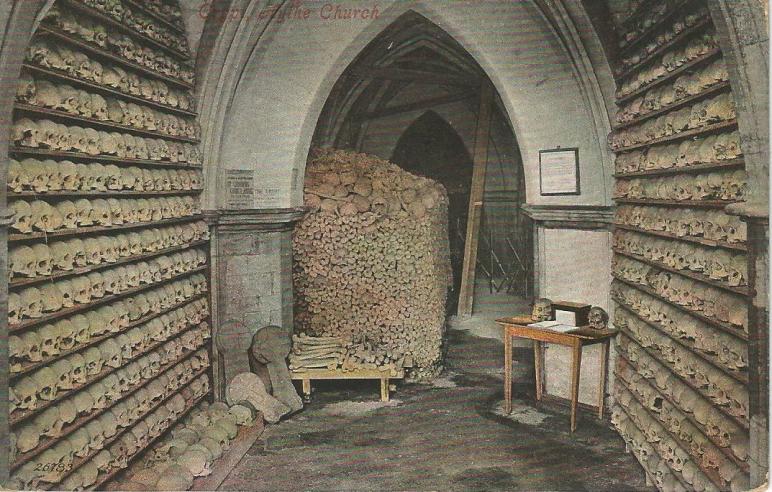

St Leonard’s has one peculiarity, found in only one other church in England – an ossuary. Known as ‘the crypt’, even though it is not, the collection contains over a thousand skulls and innumerable long bones, all neatly stacked. Earlier historians have described them as the remains of Danish pirates, men who fell at the Battle of Hastings or victims of the Black Death, without any substantiation for these claims. Today, work is concentrating on scientific analysis to establish the bones’ origins.

Thomas interested himself in the bones, too, and published a booklet entitled The Crypt of St Leonard’s Church and the Human Remains Contained Therein. He came up with the novel conclusion, based on no evidence whatsoever, that when Hythe’s three other parish churches had fallen into decay, many centuries since, their graveyards had been dug up and the bones removed to St Leonard’s.

The pamphlet written by Thomas Hall on St Leonard’s Crypt

His other achievements while in office were to stop people grazing sheep in the churchyard, to be a trustee of St Bartholomew’s almshouse in Hythe, and to introduce St Leonard’s Parish magazine, a publication which still thrives today.

Over the years, he was offered other, more lucrative benefices, but refused to leave Hythe. His health started to fail in 1898 when he resigned as Chairman of the Trustees of the Hythe Hospitals. (1) He spent sometime in Switzerland in an attempt to recover, butthe next year he applied to the Archbishop, Frederick Temple, for permission to resign his living, as he felt that he could no longer serve the parish as he wished. The Archbishop thanked Thomas for the ‘long and excellent service’ he had rendered to the church and accepted his request.

The parish raised enough money to buy him a Bechstein Grand piano, present him with a cheque and make a present of bangles to his wife. He was also given a magnificent illuminated copy of the address made to him when he left, with pictures of the church before and after its restoration.

After a period of rest, Thomas recovered enough to be appointed to the benefice of St John the Baptist, Dodington, near Sittingbourne. He found the church falling into disrepair and so started on another full restoration project. He eventually retired to 15 Castle Hill Avenue in Folkestone, where he died.

His funeral at St Leonard’s seems to have been marked by real sorrow at his parting. The great and the good of the town gave eulogies, the grave was lined with cypress and laurel, and on Sunday, a muffled peal was rung by the church bell ringers and the flag on the tower was flown at half-mast.

Thomas had met Charlotte in Hythe, and was married in the church here. All nine of his children were born in Hythe. In his retirement in Folkestone he was a frequent visitor, and he often said that Hythe was his real home. The great achievement of his working life, the remodelling of St Leonard’s was completed here, and it was St Leonard’s he chose for his last resting place. He clearly held the church, and the town, in great affection. The words ‘safe home at last’ on his gravestone surely have a double meaning.

Charlotte Sophia Hall nee Sangar was born at Shadwell Rectory, the only daughter of Benjamin Cox Sangar and his wife Charlotte nee Fothergill. Her father was Rector there from 1846-1872, before moving to St Leonard’s Church in Hythe, where he was vicar from 1862 to 1873. Charlotte, known to her family as ‘Lollie’, married Thomas Hall on 6 June 1873 in St Leonard’s church Hythe, in a ceremony officiated by the chaplain to the Archbishop of Canterbury. Perhaps her father was too ill to conduct the service himself, though he acted as a witness. He submitted a request to resign his living in the same week as the wedding, and retired to Eastbourne, where he died six months later.

Over the next nineteen years, nine children were born to Thomas and Charlotte, six daughters and three sons. Thomas had started life signing himself ‘Thomas Hall’. On his marriage certificate he was ‘Thomas Guppy Hall’, but in 1911 he signed his census return ‘T.G. Sarsfield Hall’. His sons added a hyphen and the family name became ‘Sarsfield-Hall.’

When Thomas died, Charlotte moved to Tunbridge Wells where she played a full part in civic life, particularly in the Girls’ Friendly Society, The Mothers’ Union and the women’s’ branch of the Conservative Party. She also continued to play competitive croquet, a sport she had taken up as a girl, and to win prizes at the All England Club’s tournaments in Wimbledon.

Thomas may have regarded Hythe as home, but perhaps Charlotte preferred Dodington. She named her house in St James’s Road for the place.

Robert Sarsfield-Hall, the couple’s eldest child, married Alice Walker. and the couple had four children.

Deborah Clare Dobson, nee Hall was born on 26 Jan 1883 and married Andrew Edward Augustus Dobson, an army officer on 10 June 1913 in Dodington church. The couple had two sons, one of whom was Peter, buried here. He was born in London and died in Canterbury.

Charlotte Hall had one sibling, Theophilus Edward Fothergill Sangar, who preferred to call himself plain ‘Edward’. He was born in 1856 and baptised in Shadwell. He attended school in Chelmsford and later became a railway clerk, living in Islington. He died in Hythe, though by that time his sister was no longer living in the town and was buried in the churchyard two days later, on 17 December 1892.

- Kent Archives EK2008/2/Book 15